The Beautiful Boring: How I Refactored a Game Without Breaking it

Can an AI Do a Boring Refactor? A Case Study in Systematic Code Cleanup

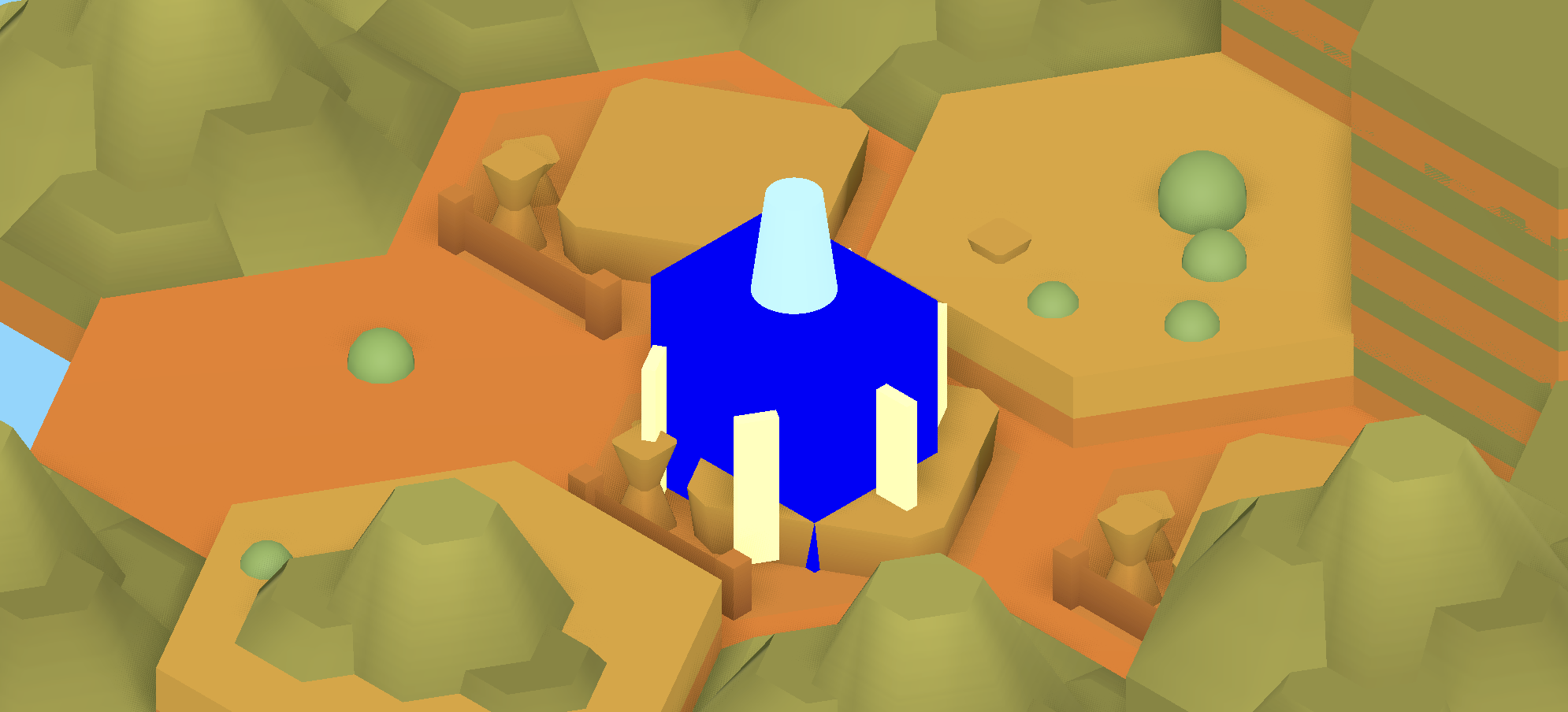

This week, my carefully-laid plans for rapid progress on Horizons Edge, a tactical wargame with card-driven combat on floating islands, collided headfirst with 2,255 lines of code and 94 functions living in a single file. Whoops. Just what I always wanted. I’d let a god class slowly brew and percolate while I focused on shipping features. Now it was time to pay the inevitable technical debt.

The wonderful file in question: game_manager.gd. It was managing twelve distinct functional areas: turn management, combat, creatures, cards, abilities, territory, players, and more. The result was tight coupling and maintenance friction of epic proportions.

The Question that drove me

I’ve spent the last month learning how to work productively with AI on complex coding tasks. And I had a nagging question: Can an AI do a massive refactor productively? Can you have a boring refactor—a by-the-numbers, tick-the-boxes, super easy, chill refactor?

This wasn’t just idle curiosity. When I last attempted a refactor of similar scope, it was an spectacular disaster. I spent two evenings fighting with Claude about types, going in circles while the AI and I kept insisting the other was wrong. The game broke for days. It was a hair-pulling nightmare that never ended. It was painful, demoralizing, and left me deeply skeptical about whether AI could handle large-scale refactoring productively. That experience shaped everything about how I approached this week.

But this time felt different. I had a plan.

Setting the Constraints

Before diving in, I wanted to be intentional. I asked Claude to analyze the file and create a refactoring plan, but with strict requirements:

Functional Requirements:

- Maintain existing behavior. No new code, no feature creep—same behavior, different structure.

- All key systems had to keep working: card play, creature combat, energy systems, turn management, terrain creation and destruction. Everything.

Technical Requirements:

- Files should be less than 400 lines each

- Absolutely no circular dependencies (this still haunts my nightmares)

- Follow good Godot practices using signal-based architecture and node-based composition

Methodology:

- Everything had to be incremental. No big bang refactors. Incremental changes mean incremental testing, which means catching bugs early.

Claude produced a 1,091-line planning document comprising 11 phases, complete with a testing strategy, regression testing plan, and a high-level architecture with 8 new manager classes. It was exactly what I needed: a detailed roadmap to follow rather than a free-form creative challenge.

The Method That Worked

Here’s the systematic approach I followed for every phase:

- Clean context: Open a new terminal window with a fresh Claude context (no conversation history creep)

- Implement one phase: Ask Claude to implement just that single phase from the planning document

- Verify no regressions: Get Claude to check to verify its work

- Create a manual test plan: Have Claude outline a manual testing plan

- Hand test and fix: Switch back to vibe coding; find bugs, fix them one at a time

- Commit with clarity: Once working, commit to the branch with a descriptive message

This rhythm was key. It prevented the cognitive overload of trying to refactor everything at once while still making steady progress.

The Results

I started Friday evening and finished Tuesday evening. Seven hours total—an hour Friday night, four hours scattered across the weekend, another hour or two on Monday and Tuesday combined.

And here’s what shocked me: the game never broke. Not once. This was the easiest refactor of such a complicated system I’ve done in my career.

The difference was night and day compared to last month. That first refactor had been a hair-pulling nightmare. The game was down for days, I was fighting with the AI in circles, nothing felt under control. This time? The game was working the entire time. Every phase landed in manageable doses. I could test incrementally. I could fix bugs before they cascaded into system-wide failures.

It’s a quintessential example of risk mitigation in action. Small, verifiable steps beat big, catastrophic swings every time.

Unlike that previous disaster, this one was systematic. Methodical. Boring, even. It felt like just a matter of following good habits and executing. No dramatic debugging sessions. No circular reasoning about types. No late-night frustration.

There was something almost boring about how well it worked. And that was the point.

What This Taught Me

The breakthrough wasn’t a better AI. It was a better process. By being intentional about constraints, breaking work into small phases, maintaining a testing regimen, and keeping context clean, I transformed a refactoring task from a high-risk, high-stress nightmare into a predictable, manageable project.

That first refactor failed because I was vibe-coding with the AI. It was reactive, unfocused, trying to solve the whole problem at once. This one succeeded because I treated it like a spec-driven project with a plan, clear objectives, and systematic execution.

The lesson: AI isn’t magic. It’s a tool. And like any tool, it works best when you know exactly what you’re trying to build and you approach it methodically.

What’s Next

Now I can finally get back to what I actually want to be doing: making Horizons Edge a better game.

This coming week: three new creatures with three abilities each. Voltage Defender (exactly what it sounds like), Biomass Tank (a tanky presence), and Flux Chaos (honestly, even I don’t know what this one is yet. That’s kinda the fun of discovery). More abilities. More discipline. More checkboxes to tick.

Until next time, may your refactors be as boring, and your code as stable, as this one turned out to be.